Geology of the Western Interior Seaway

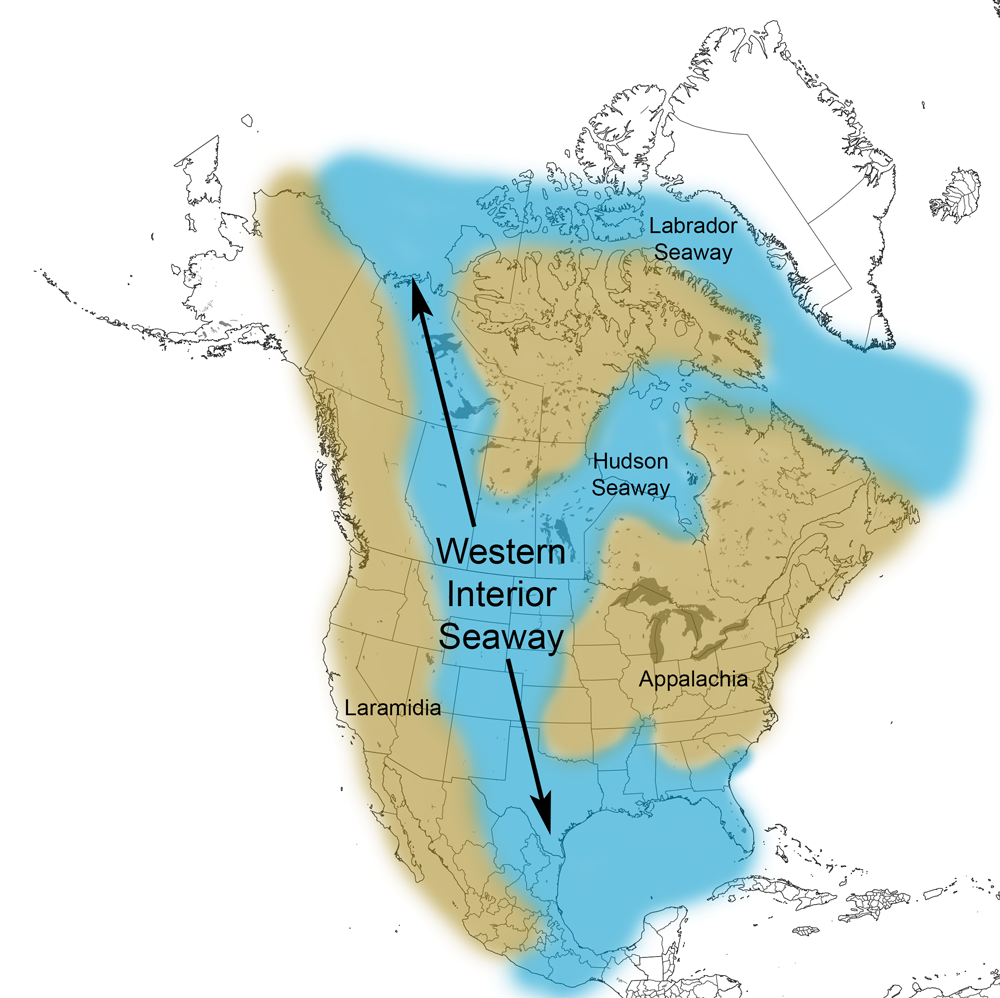

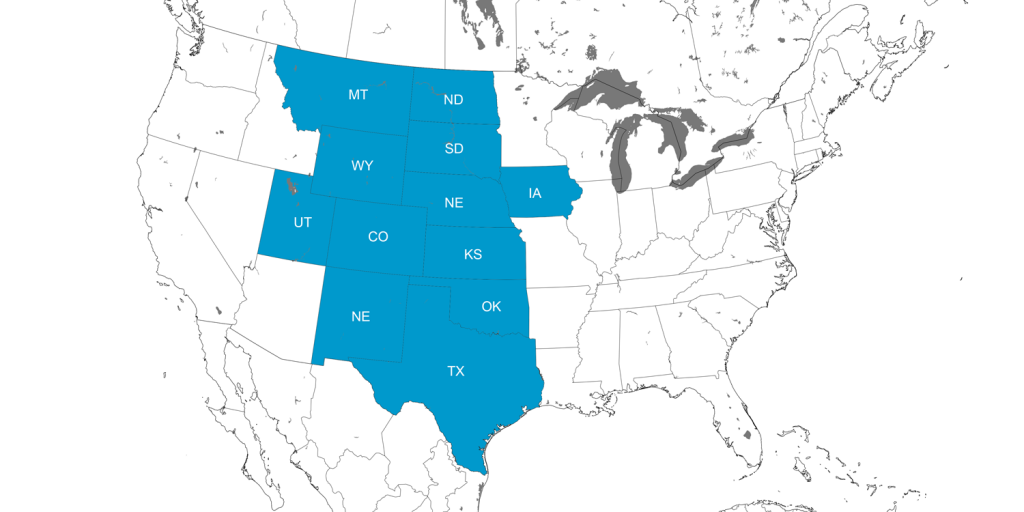

The Cretaceous-aged rocks of the continental interior of the United States–from Texas to Montana–record a long geological history of this region being covered by a relatively shallow body of marine water called the Western Interior Seaway (WIS). The WIS divided North America in two during the end of the age of dinosaurs and connected the ancient Gulf of Mexico with the Arctic Ocean. Geologists have assigned the names “Laramidia” to western North America and “Appalachia” to eastern North America during this period of Earth’s history.

Numerous species of invertebrate and vertebrate animals inhabited the WIS and left behind fossils in the sedimentary rocks that were deposited during the time of the WIS. Many of these fossils can be viewed on this Cretaceous Atlas of Ancient Life page.

Origin of the Western Interior Seaway

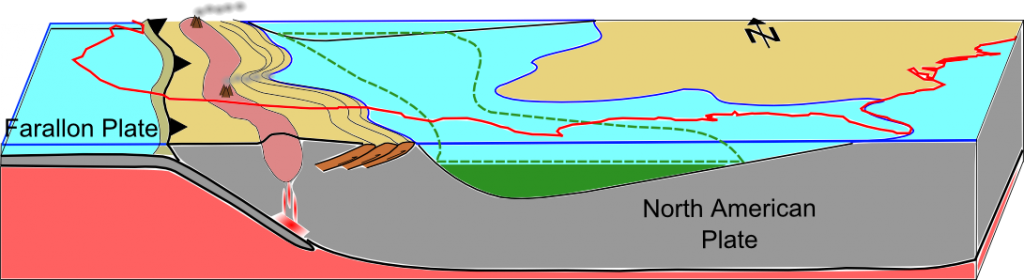

During the Cretaceous period, the ancient Farallon and Kula tectonic plates were in the process of subducting beneath the North American Plate. This caused the overlying land to warp and form a large back-arc basin. Ocean waters began to fill in the basin during a series of sea level increases (or, transgressions) during the Cretaceous. This produced the Western Interior Seaway. As the aforementioned plates subducted, they also underwent partial melting. The melt upwelled at the edge of the seaway, leading to volcanic activity that is recorded today by a series of ash layers (or, bentonites) preserved in multiple strata. These ash layers, which may be dated, are useful for stratigraphic correlation (or, matching rocks of the same age) across the WIS.

Further tectonic activity caused the WIS to experience multiple fluctuations in sea-level. Eventually, the seaway closed off at the end of the Cretaceous and gradually disappeared due to regional uplift and mountain-building on the western side of North America.

Ancient Life of the Western Interior Seaway

The waters of the WIS were warm, shallow, and inhabited by a plethora of marine animals. These included bony fish (including the monstrous Xiphactinus, or X-fish), sharks, marine reptiles such as mosasaurs and plesiosaurs, birds, mollusks (including ammonites, bivalves, and snails), and echinoderms (including echinoids and crinoids). Winged pterosaurs also flew overhead. Conditions on the WIS ocean floor were periodically anoxic (with little or no oxygen). Because of this, dead animals that sank to the bottom of the WIS often decomposed slowly, favoring their preservation as fossils.

Modern Traces of the Western Interior Seaway

Traces of the Western Interior Seaway can still be found in marine deposits throughout the United States ranging from New Mexico to North Dakota, including famous ones such as the Pierre Shale and the Austin Chalk. Some of the most notable outcrops are the Monument Rocks of Western Kansas, that are comprised of the Smokey Hills Chalk of the larger Niobrara Formation.

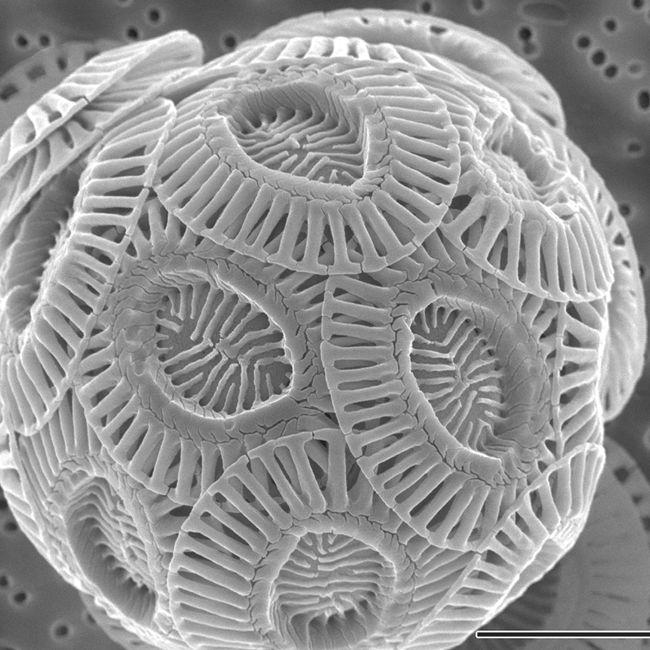

Monument Rocks is a relatively large, isolated, and weathered outcrop of chalk that preserves rock layers deposited 87-82 million years ago. The rock layers were formed through the accumulation of the remains of untold billions of small, photosynthetic algae called coccolithophores that had skeletons composed of calcium carbonate.

Coccolithophores lived in the water column during life, but sank to bottom of the sea upon death, forming large accumulations of chalk over millions of years. The chalk layers visible at Monument Rocks are the erosional remnants of a much larger outcrop belt that was scoured away by the Smoky Hill River several thousand years ago.

Sometimes called the “Chalk Pyramids,” Monument Rocks is a US Department of Interior National Natural Landmark. (Click on the image below to access a highly detailed GigaPan image of Monument Rocks that was produced by Richard T. Bryant).

Many of the incredible paleontological discoveries made by the famous Sternberg fossil collecting family in the late 19th and early 20th centuries, including mosasaurs, pterosaurs, and fossil fish, were made near Monument Rocks. These are today on display at natural history museums throughout the world.

Another famous outcrop of the Smoky Hills Chalk occurs a bit east of Monument Rocks and is known as Castle Rock. This was an important landmark on the Overland Trail, an alternative to the Oregon and California Trails, that led through the American West. (Click on the image below to access a GigaPan photograph of Castle Rock.)

Sometimes regional anoxia in the part of the WIS where the Smoky Hills Chalk was deposited led to the exceptional preservation of soft tissues. For instance, fossilized remains of cartilaginous sharks can be found, as can skin impressions of mosasaurs, and completely articulated vertebrate skeletons.

Ages of Western Interior Seaway Deposits

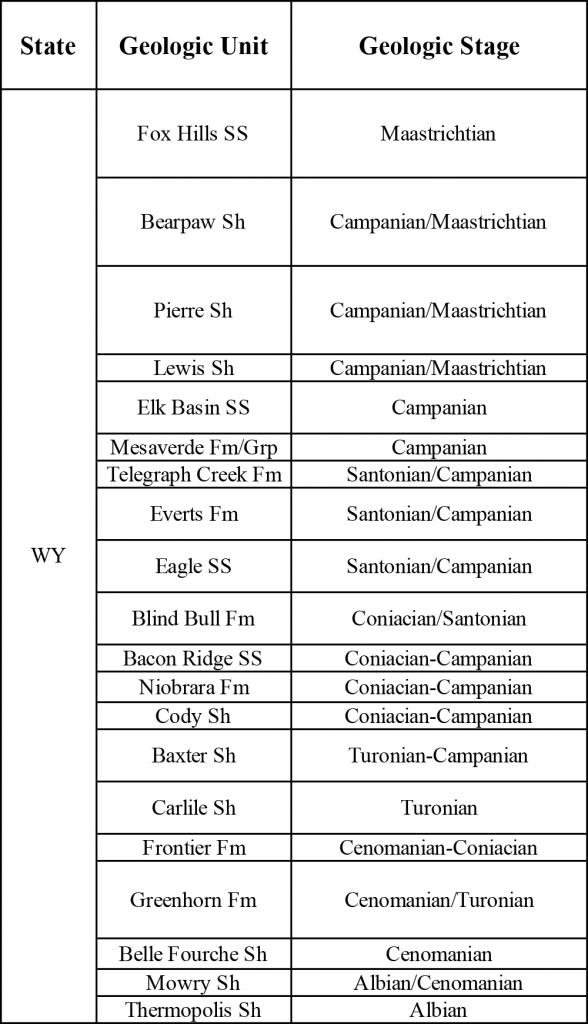

Marine rocks from the end of the Early Cretaceous and the much of the Late Cretaceous are well represented states in states once covered by the WIS.

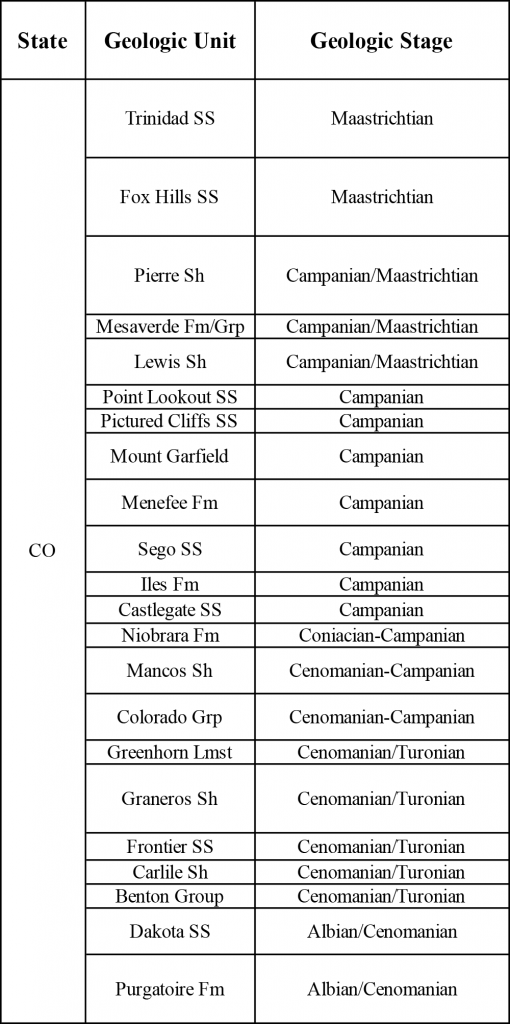

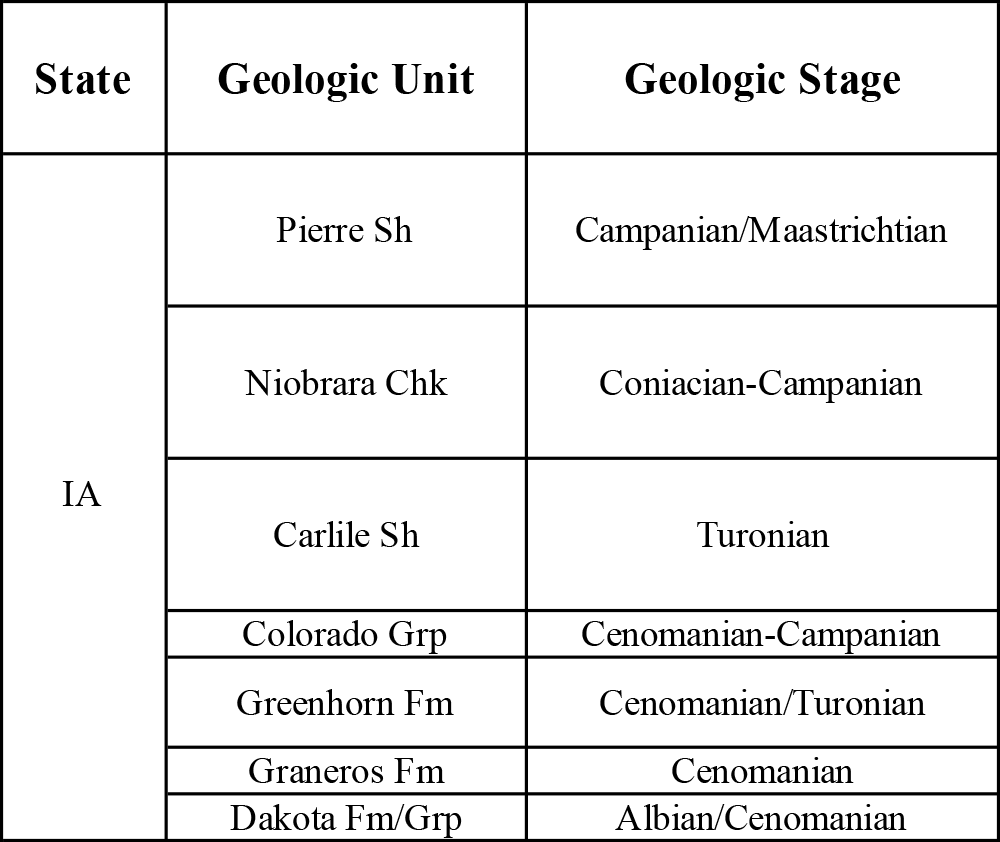

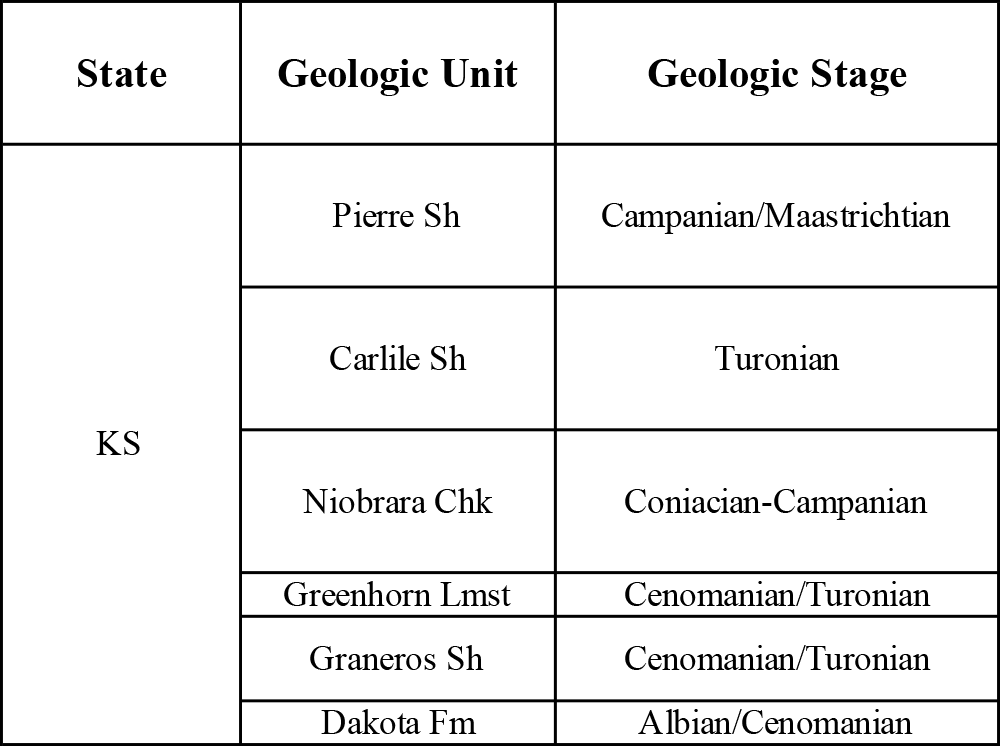

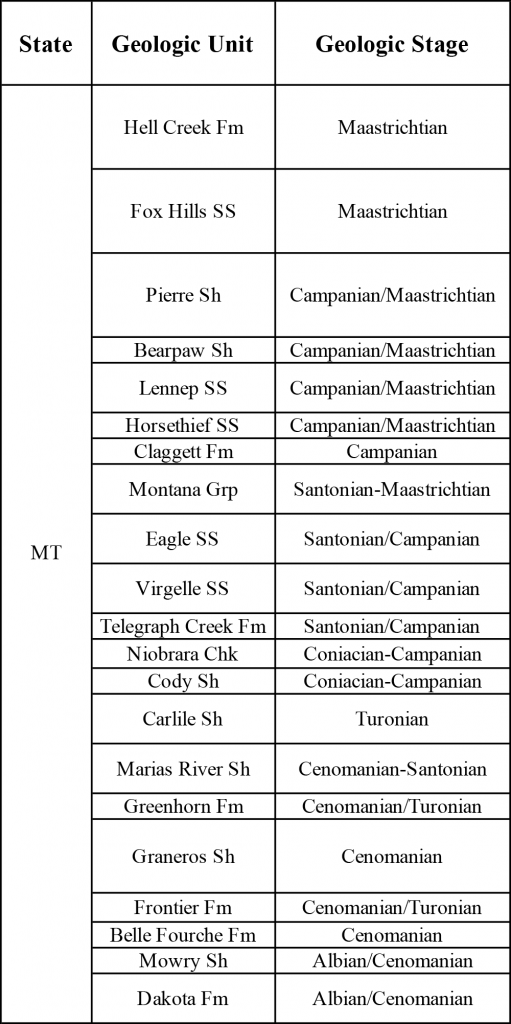

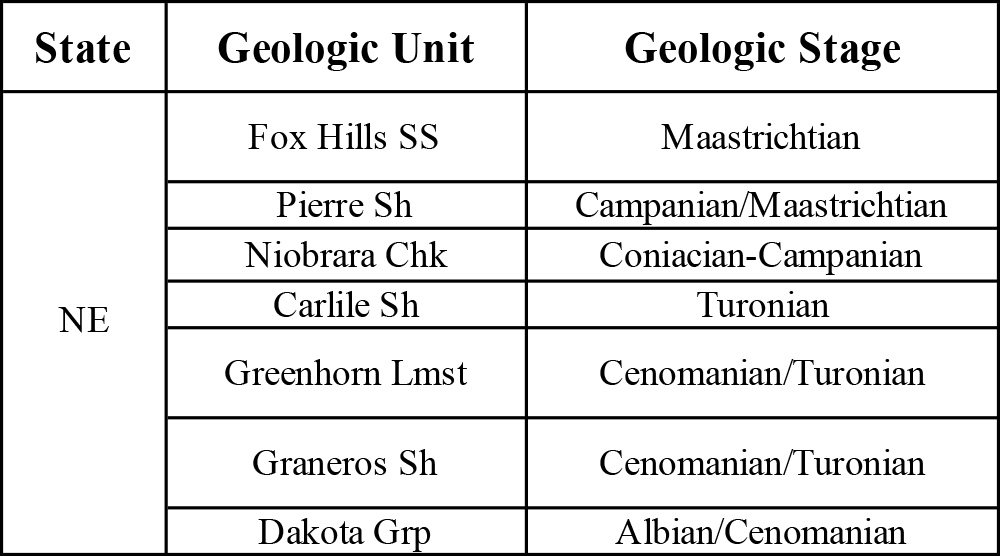

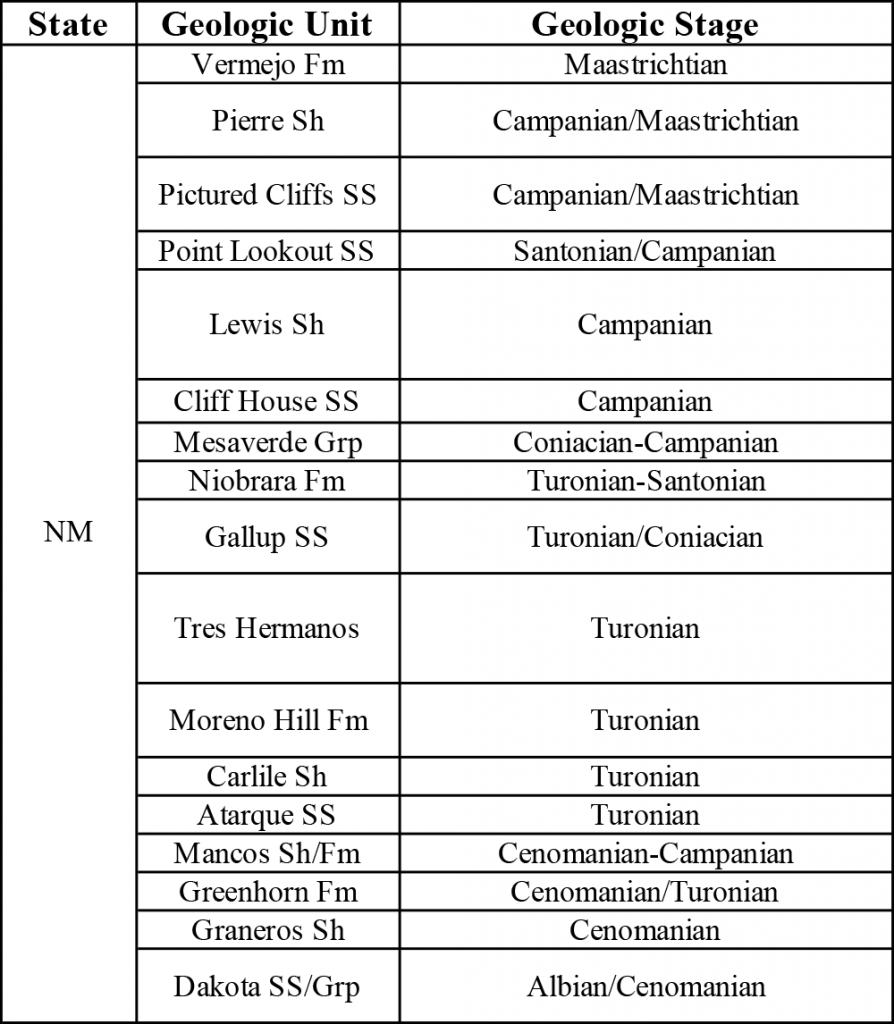

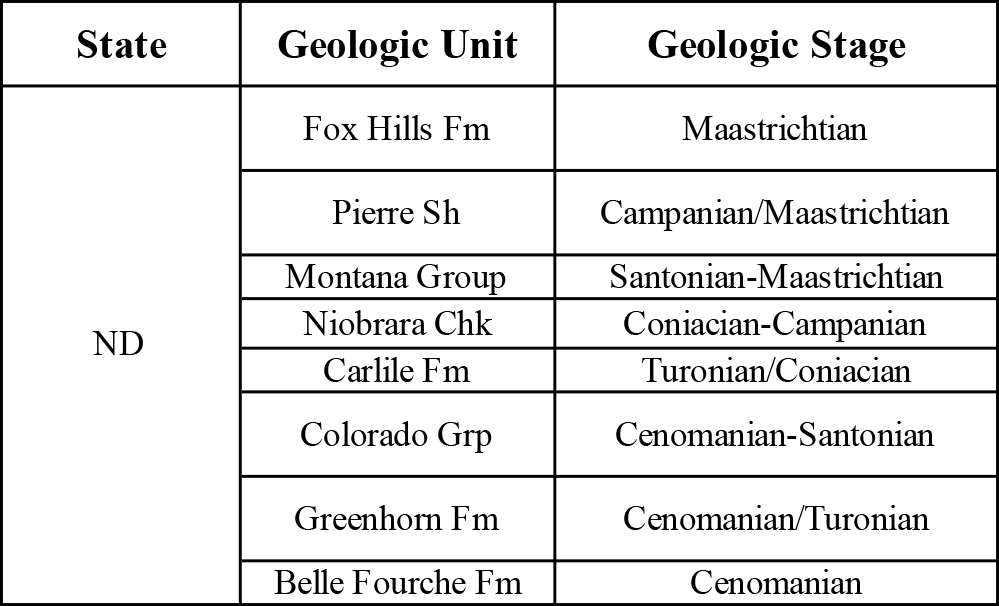

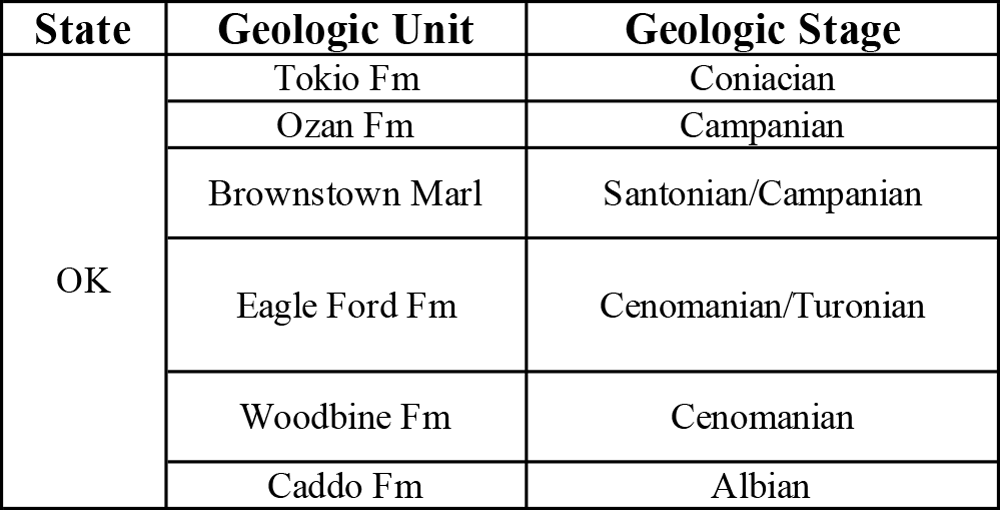

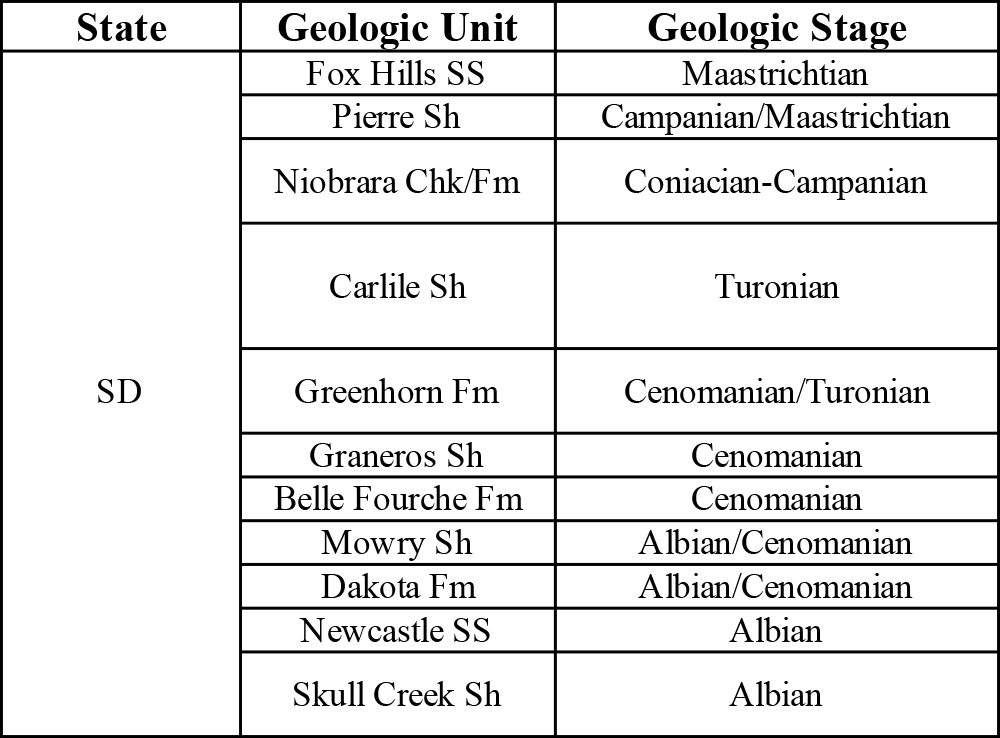

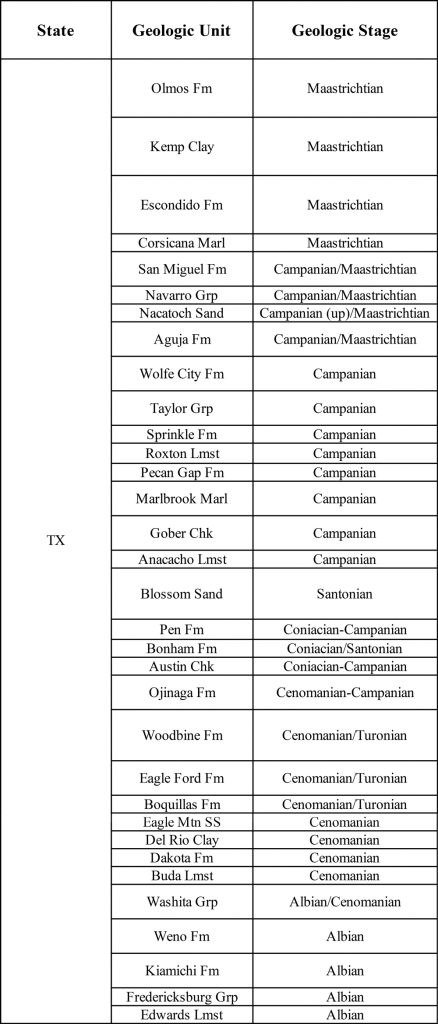

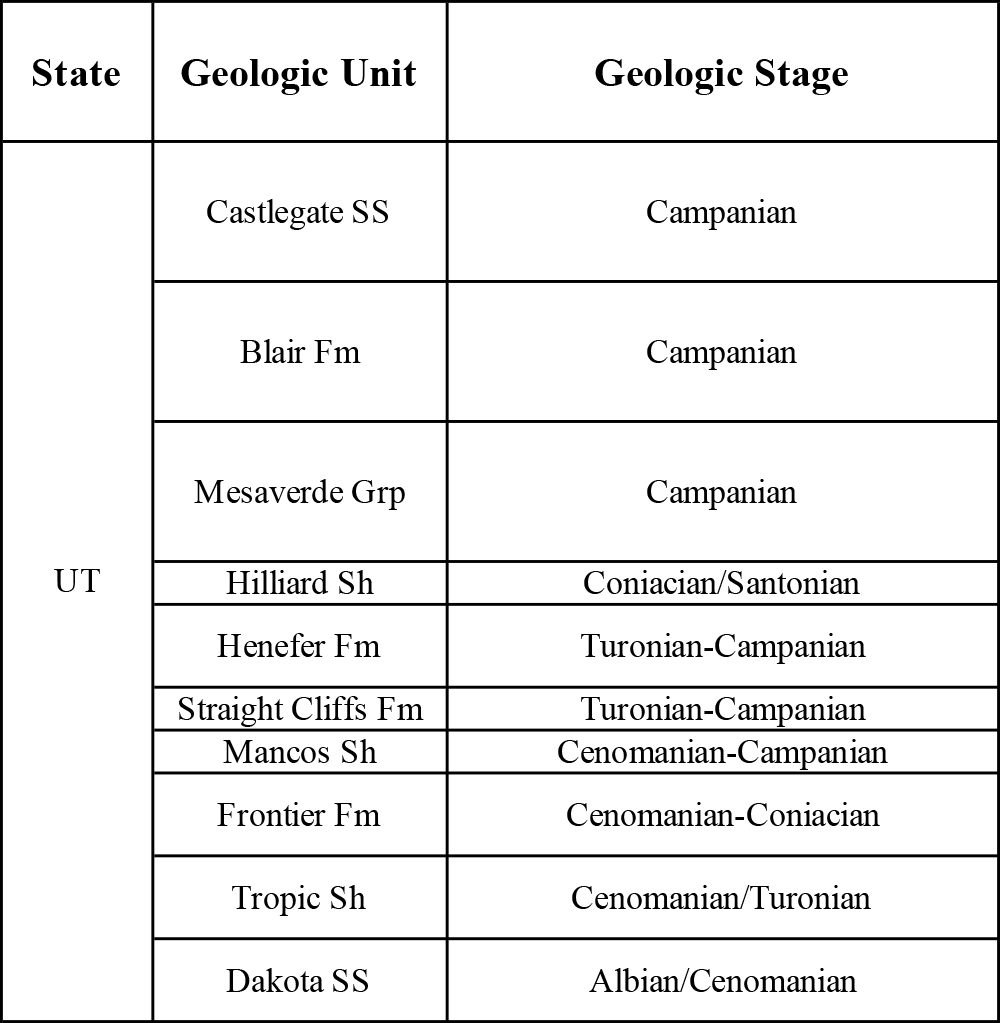

The tables below provide the geologic stages of the major fossil-bearing stratigraphic units in each of these states. The ages of these stages are:

Late Cretaceous:

- Maastrichtian: 72.1-66.0 Ma.

- Campanian: 83.6-72.1 Ma.

- Santonian: 86.3-83.6 Ma.

- Coniacian: 89.9-86.3 Ma.

- Turonian: 93.9-89.9 Ma.

- Cenomanian: 100.5-93.9 Ma.

Early Cretaceous:

- Albian: 113.0-100.5 Ma

Note: Ma = millions of years ago.

Abbreviations: Chk = Chalk; Fm = Formation; Grp = Group; Lmst = Limestone; Sh = shale; SS = sandstone.

Colorado

Iowa

Kansas

Montana

Nebraska

New Mexico

North Dakota

Oklahoma

South Dakota

Texas

Utah

Wyoming